This is delivered as a webinar (duration~ 1hr) to Network for Advanced Study of Technology Geopolitics (NAST) Fellows of Takshashila Institution on August 16th, 2025. Thanks to @rahulporuri for referring me! Sharing my script of the presentation here for other FOSS-Policy enthusiasts’ perusal.

Feel free to highlight any mistakes, gaps and areas of improvement. We could use this thread for FOSS-Geopolitics discussion.

Link to the Webinar: NAST Masterclass - Openness as a Strategic Choice

I’ve been a student of Political Science and International Relations during my brief saga with the UPSC Civil Services Examination. My work-life was around open-data and advocating for open-source (OS) with the governments. In that advocacy, I argued for OS with local city governments and state governments by putting it forward more as an “economic choice”. There are numerous practical reasons why a government/company should use/develop OS. Faster innovation cycles, security, trust, cost effectiveness, avoiding vendor lock-ins, etc. This is the first time I’m advocating for OS as a “strategic choice” for national governments. And for the purposes of this talk, I’ll take a broader view of Open-source ecosystem. It would include open software, data, hardware, standards and science.

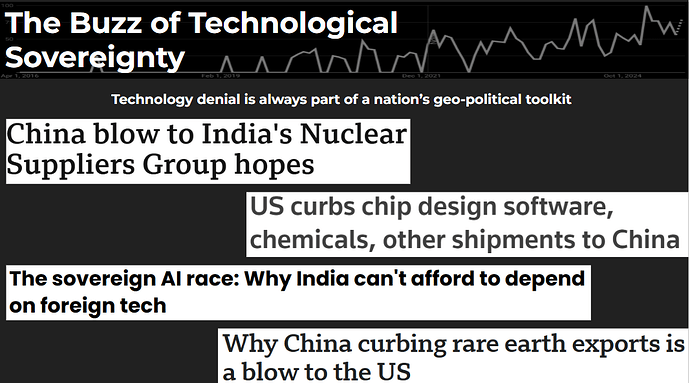

The Buzz of Technological Sovereignty

Technological Sovereignty is a buzzword in Geopolitical community now. Google trends data shows a significant uptick in people searching for this word after COVID-19 or Donald Trump’s first term as the US President. In the Paris AI Action Summit, President of France, Emmanuel Macron stated that AI Sovereignty is one of the France’s strategic goal. India has been talking about Data Sovereignty and is pushing for data localisation. The USA wants Semi-conductor Sovereignty. China wants Cyber Sovereignty. It’s definitely a buzzword!

When countries think in terms of Technology Sovereignty, it often means that they wants to own and control that piece of technology within their borders. They are insecure losing edge in these technologies to any other country. This zero-sum approach leads them to deny technology and knowledge sharing to other countries. Knowledge sharing is key for a thriving open-source ecosystem.

This is not new. Countries historically denied technology. Ancient China guarded their silk technology for years with death penalties for tech leakages. Modern China actively tried to deny India’s entry into Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) to deny India some part of nuclear technology. Very recently, USA denied design software to China.

“Open” counter to technology denials, foreign dependence and geopolitical risks

In the light of these technology denials, countries have two options:

- Playing catchup by reverse engineering the technology and developing it locally, often in a closed way. This would also include IP thefts.

- Developing open-source models of these technologies with global cooperation as a counter to proprietary technology that is being denied.

The story of HarmonyOS by Huawei explains this second option better. In 2019, Huawei fell under the axe of Donald Trump’s tech-war with China. As a consequence, Huawei was banned from using Google’s Android (not the core opensource android). It was considered a big blow to Huawei and also to China. Cut to today. Huawei developed HarmonyOS with its core components open sourced.

A question remains. Why did Huawei take the open-source route? Why did it not make it a proprietary software? My guess is that it actually speaks the strength and practical benefits of developing software in the opensource model. Also, there is suspicion on China and Huawei that they would use their technology across the world for surveillance and other notorius purposes. This open-source route would help them allay those fears and aim for global expansion- which a few US lawmakers don’t like to happen..

In the report, Software Power: The Economic and Geopolitical Implications of Open Source Software, Alice Pannier called this China’s nationalist approach to open-source. China’s 14th Five Year Plan (2021-25) mentioned open-source as a national strategic priority. Its Ministry of Industry and Information announced a goal to create 2-3 open-source communities with international influence.

It is not China alone going this route. Many countries are banking on open-source models to counter the geopolitical risks and foreign dependence. Europe announced Gaia-X as an open cloud infrastructure model to reduce dependence on AWS, Azure and Google Cloud. Though open, it would be maintained by the Europeans to safegaurd Europe’s cloud sovereignty based on European values. Though early, India wants to use RISC-V open architecture of micro-processors (SHAKTI, VEGA) for “semiconductor self-sufficiency”.

Open-source as a diplomatic tool

Beyond being a counter to technology denials, open-source models also offer a lot of opportunities to countries in what is called tech diplomacy.

Capacity-building is India’s favorite diplomatic toolkit. India built schools in Afghanistan, helped countries conduct censuses, conducted technical tranings in Africa under ITEC program, etc. Opensource models fits this model well. The strength of ppensource software in Computer Science education is already well establised. Countries’ technological capacity would be better enhanced if they are more exposed to open softwares, hardwares and standards, instead of getting locked into proprietary solutions.

Opensource model of technology can be imagined as Technological Non-Alignment Movement (NAM). During the cold war, many third-world countries did not want to get into the fight between the USA and USSR and started NAM. There is a similar threat lurking today. Though promoted by the USA, OpenRAN offers such opportunity in telecom sector. Instead of getting locked into any of the major RAN providers, OpenRAN allows countries to design their telecom sector by choosing from a larger set of vendors who folow the OpenRAN standard.

Opensource communities can serve Track-2 diplomacy, which rely on informal communications between professionals of different countries. It would also contribute to soft power matrix of a country.

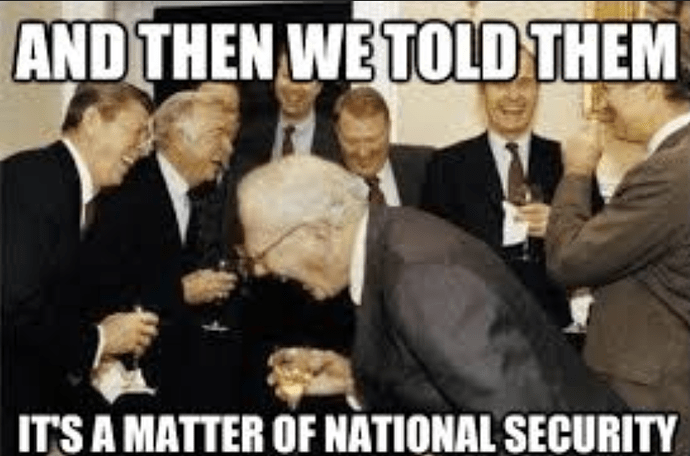

Weaponisation of open source

Countries can make a national security issue out of anything. When they could make imported cars and dating apps an issue of national security, what is there to protect open-source?

Since commerical companies are involved in maintaining and hosting many open source softwares, countries can use the same technology denial tool that we’ve previously discussed. GitHub banned its operations in Iran, Crimea, Syria due to US trade sanctions. NGINX suspended its operations in Russia. Linux Foundation issued guidelines to open source developers to avoid contributions from countries that are under sanctions. All of this is unfortunate and is affecting the very definition of open-source.

Trust on open-source would also reduce due to its weaponisation. It is reported that the US government is now auditing contributors nationalities to decide if its a secure software or not. If a lot of contributors are from Russia or China, that would probably raise a red flag. Actions like turning software into protestware would further exacerbate this trend.

It raises a question if all of this is eventual. The USA and its trans-atlantic allies dominated in open-source contributions historically. But off late, contributions from China, India and Russia have increased. So is it just the natural extension of political distrust that is now creeping into open source software? What happens to the dream of open source as a global commons then?

Technological sovereignty as ability vs autarky

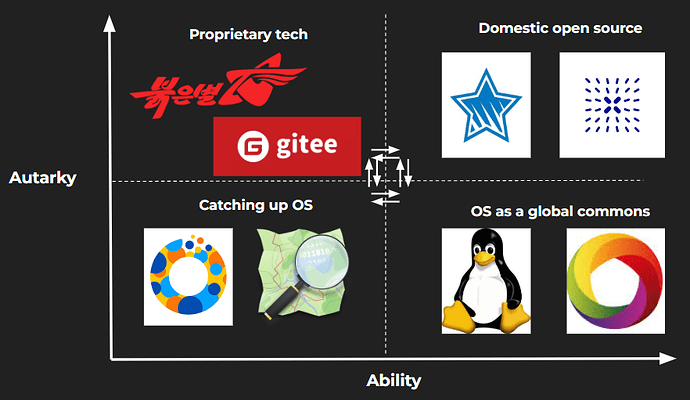

In a paper, “Technological Sovereignty as Ability, Not Autarky”, the authors re-define technological sovereignty from a zero-sum approach to a competence-based definition. Under this re-defintion, a country is still technologically sovereign, if it is competent in a technology, immaterial of its exclusive control on it. Here’s a small framework that analyses countries’ opensource strategies under this re-definiton.

- Proprietary tech | High Autarky- Low Ability: There is zero scope for open source here. Countries want to control the technology that is being used by their citizens, even at the expense of the ability of the software. One extreme example of this is RedStar OS, the Operating System used in North Korea. It is designed to surveil their citizens.China developed Gitee as an alternative to GitHub. It is not only a proprietary software like GitHub, but is also being used to censor open source code.

- Domestic opensource | High Autarky- High Ability: Countries want to develop good software and technology but wants to protect it from being abused by external elements. We can imagine it like governments being the maintainers of open source projects. Gaia-X is a good example which wants to enshrine European values in the project. Astra Linux, Russian Linux based operating system would also fit in this quadrant. An extreme version of this would be a country keeping a software open only to its citizens. That would lead to internet splitting into splinternets.

- Catching up OS | Low Autarky- Low Ability: These are opensource projects that are not tightly controlled by any government but are still yet to find great traction. MOSIP, an open source digital public infrastructure (DPI) inspired from India’s Aadhar, would fit in this quadrant.

- Opensource as Global Commons | Low Autarky-High Ability: Projects like Linux that have no governmental control and gained wide international adaption.

As the geopolitics play out, projects from one quadrant would move to the other. Will the values of opensource withstand these geopolitcal storms? I guess we will have to wait and see.