I’m usually well prepared for my content consumption during travel but I underestimated how addictive of a book Hail Mary by Andy Weir will be. I finished it up much earlier and was left with nothing to do on a 3 hour long flight. Hopelessly, I scrolled through my phone downloads to find something interesting. And that was how I read the Open Source in Entertainment report by Academy Software Foundation!

Below is a (slightly opinionated) summary of the report but I highly recommend reading the whole thing. If there’s anyone you can trust to write an engaging and far from boring report, it’s the Academy.

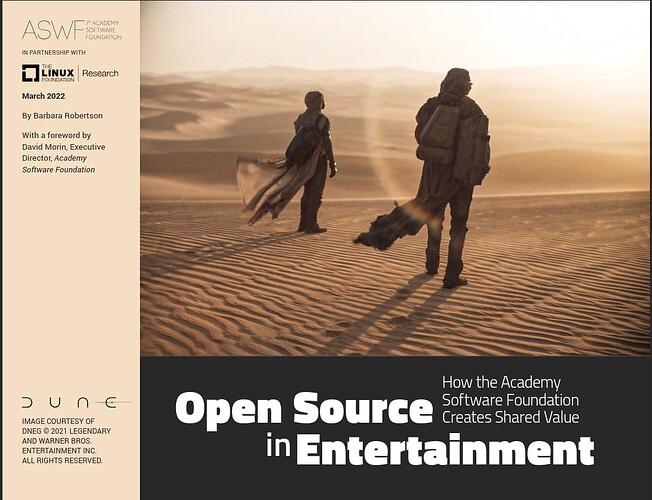

Foreword

The Academy Software Foundation was created four years ago by a group of like-minded technology executives and software developers who saw a need for a neutral place, a common

ground, where studios and vendors could come together to write open source software that would benefit everyone.

A lot has happened in this short period of time. This document the first Open Source in Entertainment report, tells the story of the Foundation: where it came from, what it has achieved so

far, and where it aims to go next.

This is a story about a community of people that generates a tremendous amount of value around open source projects, by developing some of the software components that power

all productions, and the open standards that we need for our industry to grow.

The Beginning

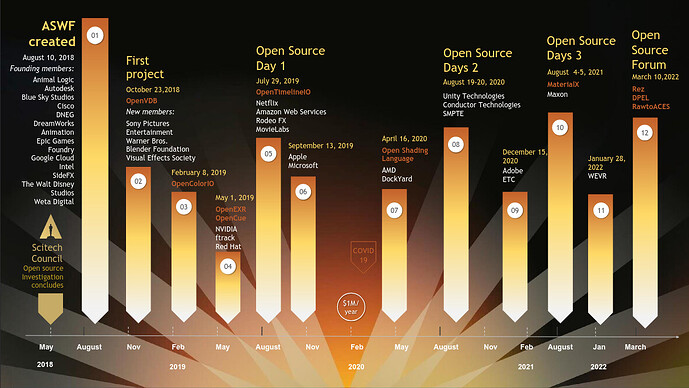

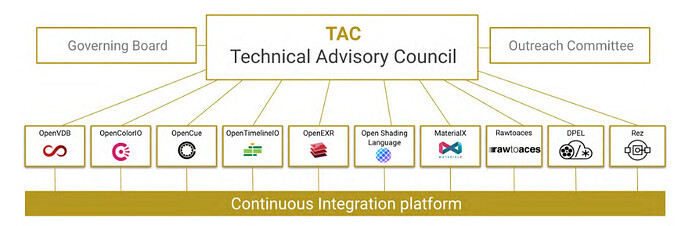

The AWSF foundation has adopted 10 open source projects in the last 4 years. The foundation has become a way for companies to ensure collaboration and innovation; and a home for OSS projects.

“The Foundation quickly got to the point where now we wonder, ‘How did we ever survive before? How did we get this stuff done that speaks to the central role the organization

plays in our day-to-day operation?’,” says Larry Gritz, software engineering architect at Imageworks. “We’re only a couple years in, but it feels like the Foundation has been there forever

because it’s so critical.”

"Before,” was July 16, 2018, a scant four years ago when the Foundation was officially launched. But the road to open source in entertainment began some 20 years earlier.

Disruption

The 1990’s were an exciting, inventive time for people creating digital visual effects and CG animated films. Toy Story, Terminator 2, Jurassic Park.

Surfing alongside all this technical prowess, though, was a disrupting undercurrent. Digital content creators other than those making films were using increasingly powerful personal

computers. So, too, were other industries. And people had begun talking about a more flexible open source operating system called Linux.

Moving to Linux

SGI (Silicon Graphics) used to be the primary service vendor for the industry in the 90s and early 2000s.

From Wikipedia -

For eight consecutive years (1995–2002), all films nominated for an Academy Award for Distinguished Achievement in Visual Effects were created on Silicon Graphics computer systems.[74] The technology was also used in commercials for a host of companies.

SGI was a promoter of free software, supporting several projects such as Linux and Samba, and opening some of its own previously proprietary code such as the XFS filesystem and the Open64 compiler.

But as cheaper PCs began to compete with more expensive ones in terms of Graphics, SGI began focussing more on broader issues (and clients) and the entertainment industry realised they could not rely on them.

We wanted to move to Linux,” Feeney says, “which is open source. But the software vendors were resistant to supporting a whole new ecosystem and figured we couldn’t do without

their animation and digital content creation tools. So not supporting Linux was considered low risk for them. We needed a production-ready alternative.”

Next is perhaps the best thing I’ve read this month!

In June 2000, 23 companies signed a commitment to move to Linux, no matter what. If the commercial software vendors refused to provide Linux support, key companies agreed to offer executables and keys to their proprietary software to visual effects and animation studios: Pixar’s RenderMan, ILM’s Zeno pipeline, Rhythm & Hues’ modelers, and RFX/Silicon Grail’s compositor. The combination would make the commercial software less necessary. Word spread about the industry cooperation and the commercial software vendors agreed to attend a meeting.

“We said we were moving forward with or without them,”Feeney says. “And that’s how as a group we got onto Linux.

So, the studios continued using a pipeline made of commercial software and their own tools built from scratch. Among the engineers, though, there was a growing realization that sharing

fundamental technology would be an advantage, and some studios released tools as open source — tools they continued to own and support.

Moving in Lock Step

Whilst the industry collectively started using Linux from this point on, the number of versions and distros of Linux available became a challenge.

“It got to the point where you needed different workstations to do color

grading and animation because there were so many versions of Linux,” says Ray Feeney, founder and president of RFX, Inc

A working group of major software vendors was established to align Liunx Support, which led to the creation of the VFX reference platform.

Early Open Source Tools

EXR was developed at ILM in 1999 and first used for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s stone. They (ILM) offered to open the source code to EXR for the community, which became what was the first open source visual effects software - OpenEXR. This set off a chain reaction encouraging other studios to open source their internal tools, notably OpenColor IO (Sony Pictures) and (Open)VDB (DreamWorks).

Once everyone started using these projects, feature requests and issues started to arise. And the industry discovered a con of managing OSS projects.

Rod Bogart left ILM in 2005, but Kainz continued to support

OpenEXR at ILM.

“For the next seven years or so after we released it, I was working on OpenEXR at least half of the time with some periods where I was working on it full time,” Kainz says. “OpenEXR continued to grow. There are always things, no matter how careful you were when you designed it, that aren’t quite right or new features that people want, and you have to think really carefully about how you’re going to add those without breaking compatibility and without cutting off avenues

to implement even more features later. Sometimes outside people would contribute some amount of code that had to be integrated, but for quite a while, it was mostly that people would request features and we’d figure out how to add them.”

In 2013, Weta added deep image support to OpenEXR resulting in version 2.0 and Dreamworks contributed a lossy compression mechanism.

And then, in 2014, Kainz left ILM.

“OpenEXR was ubiquitous,” Pearce says. “But after the maintainer left the company, eventually it was sitting there without anyone taking as much care of it. Everyone was depending on it, but people were making changes that weren’t compatible. We realized it would cease being a standard. Then a couple years later, Ken Museth said he was leaving DreamWorks and I thought, ‘Oh boy. This is like ILM with OpenEXR. The expert is going to be outside the company.”

The same thing happened with OpenColorIO.

“The original author of OpenColorIO left the industry,” Gritz says. “The project was stalled. It wasn’t in as bad a shape as OpenEXR, which was beginning to get nastygrams from Linux

distributions. People were starting to file security issues. If a company like Autodesk, which sells to the government, too, decided to drop support because of security risks, it would have defeated the original goal of OpenEXR being a common format. It was a scary cliff.”

The studios now faced a new problem. They were still committed to using Linux and creating/using Open Source Software but the sustainability of these projects (that often relied on one person at one studio) was a major question. They feared they’d have to go back to their old ways of making in house software and plugins.

Joining together

In June 2016, the Academy’s Science and Technology Council began an investigation into the use of open source software in the motion picture industry.

A survey by the Academy’s SciTech Council found that almost 84% of the industry used open source software at that time, particularly for animation and visual effects, but barriers to

adoption included siloed development, managing multiple versions of OSS libraries (versionitis), lack of governance and confusing licensing models. These needed to be addressed in order to ensure a healthy open source community.

They started organising summits to bring together the industry and discuss the problems and solutions at hand.

At the first summit, attendees asked the Linux Foundation to develop an independent analysis of the industry’s open source ecosystem. The analysis presented at the second summit on August 3, 2017, recommended the creation of a software foundation for open source projects developed in the motion picture industry. The attendees voted for the Linux Foundation to lead the development of a proposal to set up a motion picture software foundation.

The Linux Foundation started working on the project and proposed structures for governance, infra and legal services that the foundation will require.

Helping facilitate the work streams was Mike Dolan, senior vice president of projects at the Linux Foundation. “The thing most interesting to me was that the request came from developers,” he says. “It was not at the CSO (chief strategy officer) level who would have to sell it down the orga-

nization. The request came from technical leaders involved in movie creation. They wanted to build open source libraries, but had no idea how to sell the idea and get others to agree.

Overprotective lawyers told them they couldn’t do that. Business managers cared only about the next movie. When a visual effects person tried to talk to them about tools, they had no idea what they were talking about. They’d say, ‘You want us to sell our IP? Why would we do that?’ It took time.”

“This was the whole industry having the conversation together,” Dolan says. “We opened the doors to rational discussions that weren’t there before. The fundamental argument was that this is bigger than any one company. Can we facilitate an environment, share code bases that can be fundamental building blocks and reduce costs? I don’t think anyone had made the business case before.”

But what convinced the lawyers?

The Formation of the Academy Software Foundation

The engineers were the ones who convinced the lawyers we should do this,” Dolan says. “They had been so segmented from legal counsel, they hadn’t known where to go. The only lawyers they knew were patent attorneys. The engineers were frustrated by having to rebuild tools, rebuild the plumbing, because it took resources away from creating the next great innovation. But lawyers are risk managers and the business side didn’t understand, so it was up to the engineers.”

At the third summit (after LF’s presentation of the working model/charter of what the foundation will look like), a non binding poll resulted in an alliance of 19 members cumulatively funding USD 650,000. Today, they have 40 members!

Projects

Today, the Foundation has four adopted projects. OpenEXR followed OpenVDB, as did OpenColorIO, whose design and development at the Foundation is led by Autodesk. OpenCue

for render management from Imageworks became the fourth adopted project.

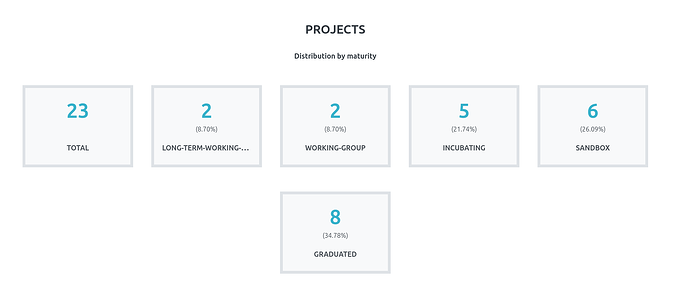

Today, AWSF has 8 graduated, 5 incubating and 6 sandbox projects - Projects - ASWF

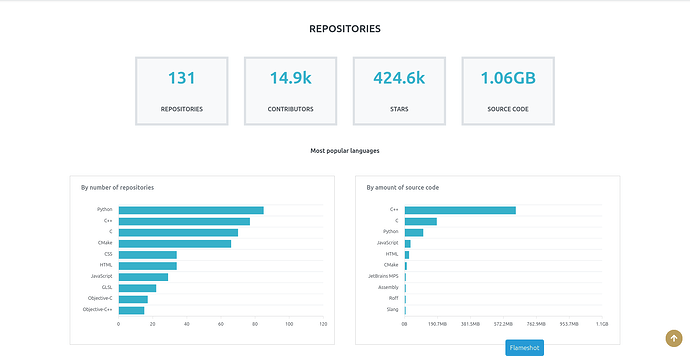

Check out what their Open Source Landscape looks like -https://landscape.aswf.io/

Contributing

Any engineer anywhere in the world can make corrections and have their ideas implemented,” Bredow says. “We’re making it easy to contribute to open source. You might think you have to

be the best coder in the world, but most people can contribute in one way or another whether that’s fixing a bug, writing documentation, or doing something more substantial that requires specific skills. Making the tools and process as accessible as possible to a wide group. It’s been a game changer.”

“We rely on member organizations to keep the lights on and grow the foundation,” says Kimball Thurston, head of engineering at Weta Digital. “But there is no barrier at all to contributing.”

As an example,

“J. T. Nelson is a collaborator who wants to push open source forward in storytelling,” Thurston says. “He isn’t currently part of a paying member organization, but he comes to the meetings and contributes and we listen to what he has to say. He helped get a Jupyter notebook preview going for Universal Scene Description (USD) so you could see how a web-based pipeline plays with USD in the browser. It was super cool. He just showed up and did that.”

Leaning in

Corporate accountability and giving back (to and for the right reasons) is an incredibly important factor to evaluate how sustainable OSS ecosystems are and this section shows the foundation is doing something right.

“We all use these projects,” Bogart says. “We want to make sure we all have access to them and they continue to work and are kept up as the world changes.”

“If I had to pay a company for every instance of an OpenEXR reader we had, my costs would spiral out of control,” Pearce says

“We want to create the very best images in the most efficient manner possible with tools we can all use and enable us to share things back and forth,” says Jordan Soles, vice president of technology and development at Rodeo FX. “The ability to share between studios is in part built upon a lot of the open source software and principles that exist. If you’re able to share things and pull them into your system quickly, you’ll definitely see that extra time on the screen.”

“We are successful as a software company in the M&E space because the ecosystem itself is healthy,” says Eric Bourque, senior director, engineering, entertainment & media at Autodesk. “Making the case for why we should have our full-time engineers write code everyone can use freely required a shift in thinking. Having a common foundation of components

makes everyone’s software more relevant, robust, and maintainable. Having more eyes looking at the foundational pieces makes them stronger. We provide value by building workflows on top of that foundation, by building tools for artists.”

Likewise, the existence of a foundation that acts as a safe home for these projects gives trust to the studios to continue using and creating such projects.

"The Foundation gives us trust in the viability of these open source projects. We want to make

sure these projects that sit at the center of a software stack don’t go away. The Foundation

provides a feeling of relief that the tablecloth won’t be pulled out from under everything.

“There aren’t a huge number of color scientists,” he says. “Everyone is fighting over a limited number of experts. But because of the Foundation, someone can switch companies and continue to work on OpenColorIO.”

Payne says, “Open source depends on the people who do it. I was at ILM when I first started contributing to the Foundation – helping find bugs and being a power user of OpenColorIO. Now I’m at Netflix, and I helped develop the latest version, overhaul the documentation, and re-do the

website…You feel a sense of community and responsibility to shepherd this work and make it the best it can be. Being part of that process makes me better at what I do. It’s been rewarding for me.”

Recognising Engineers

“We’re seeing a side benefit to the Foundation that in retrospect is obvious,” Bourque says. “Our internal developers love that people can see the work they’re doing. Visual effects artists can see their work on the screen in the theatre, unlike someone working on code. Now, their code is exposed and people can learn from it – they can be proud of their work because it’s out there. Others are able to benefit from their contributions, which is very motivating to the individuals working hard on these open source projects.”

Behind the Screens - ASWF gives visibility to the engineers that are making this work happen. It was nice to compare this with https://forklore.in and notice the similarities in the messaging.

Submitting a project

“We can adopt projects or create projects that respond to a need,” Morin says. “That’s our role. When a developer thinks about open sourcing software that others might need, we’re available to help, even if it is not one of our projects. We don’t take over projects. If a company wants to submit an existing project, we have a clear process for submitting. The engineers on the TAC look at all submissions, do the due diligence, and vote for adoption.”

“There was a concern with OpenVDB that we’d lose control,” Pearce says.“But you get to write the ‘constitution.’ You can specify who the benevolent dictator for the standard will be, how people can vote, and how you replace people. You set up the parameters.”

Details on how to submit projects is available at Redirecting… The form asks some general questions about the current state of the project. Accepted projects go through a phase of incubation wherein they should build an active community of contributors ensuring a steady flow of contributions. Projects are required to obtain the Core Infrastructure Initiative Best Practices Badge (from what I remember the Core Infrastructure Initiative was LF’s response to the OpenSSL Heartbleed vulnerability and then became OpenSSF.)

Here are some more requirements needed for projects to graduate out of the foundation - tac/process/lifecycle.md at main · AcademySoftwareFoundation/tac · GitHub

Working Groups Spark Innovation

Check out the working groups section for detailed information on

-

Digital Production Example Library

“We took the Moana island scene, an environment from

Moana’s home island in the movie, extracted the proprietary

code and made it more standard,” Cannon adds, referring

to Disney’s popular animated feature. “Now anyone can

download that scene and use it. I hope we’ve inspired others to

do the same. -

“Open source has the power to break down racial, gender, and

corporate barriers to unite people around a shared goal,” says

David Morin, the Foundation’s executive director.“This year we focused on women and people of nonbinary

backgrounds,” Rose says. “We put out a call saying they didn’t

need any experience to apply. Those chosen had access to

an online platform that provided a series of classes in visual

effects, a community of others doing this at the same time, a

slack channel, and a personal mentor within the industry.”

Between 25 and 30 people signed up, and at the end of the

summer, some got jobs in the industry. -

Review and Approval

“There was a feeling in the air that there is a gap that needs to be filled,” Gritz says. “The working group provided that necessary place for people to sit around the table, a neutral area where all the major players could show their hand, the

tools they built. Everyone has good ideas and we saw a trend heading toward where no one is yet there. The question is whether we can pool resources and come up with a solution that works for more than one facility. We don’t know if the solution is to build something, highlight something that’s there, gather requirements, or what. We’re still exploring, still figuring out where it will go.”

There are four other working groups coalesce under the Foundation

umbrella: CI (Continuous Integration), Python 3, Rust, and USD. Of those, USD is the most active

“USD is an enormous project, bigger than any other project in the Foundation,” says Disney Animation CTO Nick Cannon. “Pixar has the option to bring it into the Foundation, and it could end up there, but it’s quite new. It’s still being adopted, still evolving. It’s on the journey of maturing. It may not be

ready for the Foundation yet.”“It could end up at the Foundation,” says Pixar’s CTO Steve May. “We talk about it. There’s a beauty and effectiveness to the focus the Foundation currently has. The Foundation has built a great home for an important set of libraries. But,

we’re innovating very very rapidly and USD is an integral part of Pixar’s pipeline. It would be challenging for us right now to have it be completely housed somewhere else.”

USD is a good example of one way in which the Foundation

supports important open source projects when needed, even

those that are not Foundation projects.

Looking ahead

“The Foundation is young,” Bogart says. “As with anyone who is young, it’s trying to find its place in the world and find its best contribution. What is the best self the Foundation can be? I think that’s still to come. And that’s a positive statement. The Foundation has already been successful. Contributions are going on and they’re great. Now, it has the opportunity to do more, yet be specific about what that more is; to know what it’s going to be when it grows up.”

“Open source is an opportunity – anyone can get involved,” Dolan says. “The biggest problem is that there is not enough talent coming into the system. Not enough at an academic level. We’re trying to figure out how to get more people into the industry.”

“It’s a lot of work to keep the community thriving and to keep participation,” Payne says. “The same people can’t maintain a project forever. We need to get new people involved and invested.”

“Right now the bigger players are aware of the value of open source because they can’t afford not to be,” Bourque says. “Others are becoming more aware and they’re making the same observation: They’re not giving things away. They’re multiplying their value.”

Meeting small studios’ needs

Why should a small studio support the Foundation when they

can download free software without joining?

“They benefit from helping build the infrastructure,” Bredow says. “They benefit from the chance to weigh in. Companies that have joined say they were already spending as much for lawyers and maintainers as for the few thousand dollars of

sponsorship, and they got a better system in return.”

Pearce suggests that small studios think about contributing time or money to the Foundation as an investment, not a cost.

“Any small studio should understand that investing in open source is investing in their ability to make bids on shots that require interoperability among multiple studios,” Pearce says. “It’s an investment that will pay off for them in the long run.”

Conclusion

Clearly, the Foundation has become much more than the sum of its open source projects.

“Where we are today points to the future where open source software will become a strategic technology for everyone who wants to share, innovate, and develop a sense of community around software” Morin says.

“Our initial meetings were because there were a couple projects in trouble,” Gritz says. “The projects are all healthy, but that’s such a small part of what we’re doing now. The interesting thing to me is how far the organization has gone beyond that. It speaks to a hunger maybe we couldn’t put a finger on. We now have a means of communication to solve common problems, a forum.”

I’ve been disappointed with a lot of things that the Linux Foundation has been upto since the last few years so it was refreshing to see what it used to stand for (and hopefully still does). It is still surprising to me that a development like this happened in the entertainment industry of all places. They’ve taken a lot of good steps towards creating a sustainable open source community for their ecosystem and I hope this framework can help others build similar initiatives.